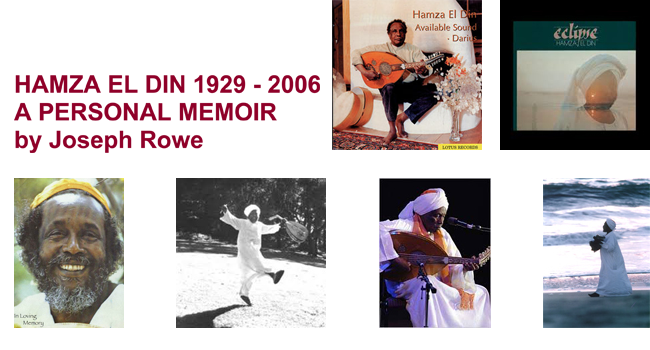

Website of Hamza El Din, one of the original pioneers of what is now called "world music."

Hamza El Din was my most influential music teacher, but he was far more than that. He was both old friend and Ancient Friend.

I mourn the passing of my old friend, but I still sense the Presence of my Friend. It happened recently, after a spasm of grief, when I suddenly decided to listen to "Escalay" again, for the first time in years ... but mostly it happens in Silence.

I first met Hamza in the Autumn of 1971. Shortly before that, I had been living in California, and had an ardent desire to learn the oud. I was mostly interested in the virtuosic traditions of classical Arabic and Ottoman styles. One day, on Pacifica radio in Berkeley, I heard a long selection from the recording "Al Oud" It was not the type of virtuosic oud playing I thought I was interested in, but it had some quality I had never heard before. As I began to really listen, I was totally captivated. To me, it sounded like a marriage of Black and Arab Africa, a marriage of painful nostalgia and profound joy, and a marriage and counterpoint of voice and instrument like I'd never heard before. Who was this guy?

"Music from Nubia by Hamza El Din," the announcer said tersely. A name which would never leave my memory. Shortly afterward, I was amazed to hear from a musician friend that Hamza El Din lived in the U.S. --- and that he was currently teaching music at the University of Texas at Austin. My home town! A further synchronicity: after months of working survival jobs in Berkeley, I had already been mulling over the prospect of going back to Austin and finally finishing my B.A. degree (in math, not in music). Soon, I packed my bags and left for Austin.

I still have a vivid memory of that first day of class in September. It was hot, as usual. People ambled in and sat down casually. The bell rang, but students were still filtering in, none of them in a hurry. Apparently the teacher was late. No problem. This was still very much the psychosphere of the sixties... I looked around. A few students were actually smoking cigarettes in the classroom (the smell of a joint lingered faintly out in the corridor). It was a very diverse group. A rainbow gathering in terms of ethnicity and skin color. Many obvious Middle-easterners. Mostly men, but several women too. Almost all the women seemed to be Persian. A small knot of rather bewildered-looking "frat rats" as we hippies called them (who, as I learned later, were there only because they'd heard it was easy to get an "A" in this course without doing any real work). Very wide range of ages also. One black guy sitting over to my right attracted my attention. He looked very hip, smoking his cigarette. So casual and relaxed, in his brightly colored, but elegant shirt and sandals. Curly long hair and beard, but different from the usual Afro-frizz. Indeterminate age --- a bit older than me, probably 35-40 years old. Must be a really cool jazz musician, I thought with satisfaction (I was an ardent jazz fan in those days). Then, when all the students seemed to have arrived, this guy stood up, walked over to close the door, welcomed us, and introduced himself in a thick, lilting accent. Then he sat down behind the teacher's desk. For the first time I looked deeply into his eyes. I'd never seen eyes like that. They seemed like windows, reaching back into a long tunnel of shadow and light, into an unimaginably distant past. Strange, yet startlingly familiar. I felt this so strongly, I remember wishing I were a painter, so I could attempt his portrait.

Hamza's approach to teaching music was anything but formal. At first I found it frustrating, and rather disorganized. You never knew what he might talk about next. One day he would be chalking out modes and musical terms on the blackboard. Another day he would decide to spend the whole class period telling us stories about village life in Nubia, before the Deluge: the cultural and ecological catastrophe of the Aswan Dam. A calamity which literally drowned the Nubian way of life, and destroyed a culture which had existed at least since the time of the Pharaohs --- yet a calamity which also allowed me to meet this exile who would change my life, like so many others who encountered him. This became evident even in his class at UT. Many rich and otherwise improbable friendships were formed among us through his influence. Because of Hamza, I met my lifelong friend Geoffrey von Menken, classical scholar, musiciologist, and master luthier, who made the superb oud I still play today.

I remember being impressed by one of his stories about how Nubians handled theft --- a phenomenon extremely rare in his village, Toshka. People never locked their houses. They didn't even have locks, though they had poor and prosperous people living together, like villages everywhere. They had no jail. Sometimes people would return home after an absence to find that a sack of rice had disappeared. But no one worried. In a day or so, the person who took it would appear, with an explanation of need, and a promise to pay it back. But on the rare occasions when it became clear that someone had actually stolen something, it also became clear to everyone who the thief was. Somehow, all the villagers knew. And the thief knew that they knew. The punishment? No one would talk to the thief. People deliberately avoided the person. It didn't take long for this punishment to have its effect: either the thief would leave and never return, or (more often) would break into tears and ask forgiveness. Which was always granted, providing the debt was honored.

There were so many other stories. And jokes. About life, about music, about dervishes, Islam and other religions, the effect of modern times... it would take a book for me to do justice to them. Finally, I began to understand that telling stories was an essential element of his teaching of music.

As well as the group classes, I signed up for individual oud classes with him (the drumming lessons took place in the group classes). Formally, I studied with him for almost two years. I learned to play and improvise in the maqamat (like modes, or ragas) of Arabic classical music. But I could have learned that elsewhere. The precious thing he gave me was a radically different approach to music. How to sum it up? "Spiritual" seems a bit of a cliché, but I don't know if I can find a better expression. I'd been encouraged by other musical teachers who perceived some talent in me, but Hamza encouraged me in a totally new way. He deeply perceived how much my playing tended to come from the head and the hands more than from the heart, and he gently urged me to always go back to my own heart, and to the heart of the music. To find deep relaxation in all my body, even (paradoxically) in the midst of intense activity. And never underestimate the value of simplicity! He also told me that whether I am playing repertoire, improvising, or composing, I should try to remember that I am only the instrument. God is the real musician. It has taken me decades to digest all this, and the process is still far from complete.

In the many years since our first meeting, our friendship became like a diamond in my life. Not that I got to see the diamond all that often. Sometimes years would go by without any contact between us, any news from him. He wasn't much of a correspondent. Once when I happened to be in San Franciso in the late '70s, he suddenly called me up and invited me to join his group onstage with the Grateful Dead, clapping the complex 48-beat cycle of the Nubian "Nagrisad" to Hamza's tar drum, singing, and Mickey Hart's percussion. It was the Dead's last concert at the old Winterland palace. Then I didn't see him for a long time, and heard he'd moved to Japan. But we always connected again, sooner or later, somewhere or other. Everytime we talked on the phone, or met (in Austin, in California, and in more recent years when he played in Paris, where I now live with my wife, singer Catherine Braslavsky) his magnificent smile, warm embrace, and teasing jokes made it seem as if no time had passed at all. It was in Paris, when he was playing in "The Persians" by Peter Sellars, that we first met his wife, Nabra. She's Japanese, but her name is Nubian, and means "pure gold" --- she has been a delight to get to know. As the years go by, I sometimes meet people connected with Hamza in some way I never knew of. A recent example is Fikri El Kashef, a Nubian musician who has known Hamza longer than anyone else I've met. Fikri is the director of an extraordinary "ecolodge" near Abu Simbel in Egypt, highly recommended for anyone traveling to Egypt, and a destination in itself. (See link here.) It is called Eskaleh --- an alternate spelling of Escalay, The Water Wheel, powerful symbol of ancient Nubian life, and the title of Hamza's most original and perhaps most profound album. Fikri is also a world-class musician, though he has recorded very little that I know of. His style of oud playing leans more toward the Arab virtuosic traditions than Hamza's but his Nubian roots are deep nevertheless. I was amazed to hear a homemade recording of Hamza and Fikri playing Escalay in an oud duo, with a very deep communication between them ... something I would have thought virtually impossible, because of the nature of that composition.

Because we live in a time of unprecedented evolutionary crisis, I'd like to add another half-forgotten memory, which I hadn't thought about for years, until I began to write this. It must have been sometime in the mid-70's. Hamza had been visiting Austin for a concert, and I think he stayed over for a visit and to give a lecture. He, Geoffrey, and I were having supper at a sandwich shop. We were talking about some of the esoteric teachings that were beginnng to proliferate in those times --- Sufi, Zen, Tibetan, Yoga, etc... All three of us had just read the first Seth books by Jane Roberts, and were discussing that extraordinary material. After a reflective pause, Hamza said:

"I wonder why all these teachings, which used to be so rare, are now being published for everyone? It's amazing to me. So many bookstores have them. Why is this happening now?"

An answer began to form immediately in my mind. In those days I was part of the majority who were worried about nuclear holocaust, as well as the minority who were already beginning to be worried about ecology. I often felt pessimistic. I told him I thought it was because the planetary situation is becoming urgent. "We now have the capability of destroying our planet, and we need all the wisdom we can get." And then I launched into a litany of the latest statistical horrors and projections. A long silence. Then I looked at Hamza. It was as if fire were coming out of his eyes. He spoke with quiet intensity, and anger:

"No! This thing you call planet is the mother of life. They will not destroy her. SHE will destroy them! The Earth will rise up and destroy all their technology and all their cities if she has to! "

I had never seen Hamza so fierce. Nor had I heard him speak about the Earth in this way. Geoffrey and I were silent.

Then, as I recall, he quietly added something like this: "It is only by the mercy of God, er-Rahman, er-Rahim, that it hasn't happened yet."

Last, but far from least: I learned something precious and inexpressible about the tasawwuf, the Sufi Way, from Hamza. Not that he claimed to be a Sufi master. It was what he manifested, what he incarnated, more than what he said. Once, he told me: "If you ever hear anyone say 'I am a Sufi', it means they're not." Some years later, I became deeply attracted to the books of Idries Shah. I mentioned to Hamza that I had learned from Shah's writings that the word "faqir" is originally an Arabic word, meaning simply "poor person" And that the concept became greatly distorted in India, with all the strange antics we associate with "fakirs". I was rather excited about this discovery. He agreed that the Indian version is a weird distortion of the original meaning. But he laughed a lot at my excitement about the etymology. "Did you know, Yusuf, that I'm a faqir ? Yes, it's almost like a family name. People don't call me Hamza El Din at home, they call me Hamza Faqir."

The faqir ideal is said to be this: never to look up to anyone whose social status is above yours, and never to look down on anyone whose social status is below yours. Hamza lived this ideal.

I feel grief, and joy, in writing this memoir .... I dedicate it to all who loved Hamza and love his music, and to his beloved Nabra....

as-salaamu'aleikum ... shalom aleichem... Peace to all

May all beings awaken to the Truth of who they are ...

Yusuf

(as Hamza always called me.)

Hamza El Din was my most influential music teacher, but he was far more than that. He was both old friend and Ancient Friend.

I mourn the passing of my old friend, but I still sense the Presence of my Friend. It happened recently, after a spasm of grief, when I suddenly decided to listen to "Escalay" again, for the first time in years ... but mostly it happens in Silence.

I first met Hamza in the Autumn of 1971. Shortly before that, I had been living in California, and had an ardent desire to learn the oud. I was mostly interested in the virtuosic traditions of classical Arabic and Ottoman styles. One day, on Pacifica radio in Berkeley, I heard a long selection from the recording "Al Oud" It was not the type of virtuosic oud playing I thought I was interested in, but it had some quality I had never heard before. As I began to really listen, I was totally captivated. To me, it sounded like a marriage of Black and Arab Africa, a marriage of painful nostalgia and profound joy, and a marriage and counterpoint of voice and instrument like I'd never heard before. Who was this guy?

"Music from Nubia by Hamza El Din," the announcer said tersely. A name which would never leave my memory. Shortly afterward, I was amazed to hear from a musician friend that Hamza El Din lived in the U.S. --- and that he was currently teaching music at the University of Texas at Austin. My home town! A further synchronicity: after months of working survival jobs in Berkeley, I had already been mulling over the prospect of going back to Austin and finally finishing my B.A. degree (in math, not in music). Soon, I packed my bags and left for Austin.

I still have a vivid memory of that first day of class in September. It was hot, as usual. People ambled in and sat down casually. The bell rang, but students were still filtering in, none of them in a hurry. Apparently the teacher was late. No problem. This was still very much the psychosphere of the sixties... I looked around. A few students were actually smoking cigarettes in the classroom (the smell of a joint lingered faintly out in the corridor). It was a very diverse group. A rainbow gathering in terms of ethnicity and skin color. Many obvious Middle-easterners. Mostly men, but several women too. Almost all the women seemed to be Persian. A small knot of rather bewildered-looking "frat rats" as we hippies called them (who, as I learned later, were there only because they'd heard it was easy to get an "A" in this course without doing any real work). Very wide range of ages also. One black guy sitting over to my right attracted my attention. He looked very hip, smoking his cigarette. So casual and relaxed, in his brightly colored, but elegant shirt and sandals. Curly long hair and beard, but different from the usual Afro-frizz. Indeterminate age --- a bit older than me, probably 35-40 years old. Must be a really cool jazz musician, I thought with satisfaction (I was an ardent jazz fan in those days). Then, when all the students seemed to have arrived, this guy stood up, walked over to close the door, welcomed us, and introduced himself in a thick, lilting accent. Then he sat down behind the teacher's desk. For the first time I looked deeply into his eyes. I'd never seen eyes like that. They seemed like windows, reaching back into a long tunnel of shadow and light, into an unimaginably distant past. Strange, yet startlingly familiar. I felt this so strongly, I remember wishing I were a painter, so I could attempt his portrait.

Hamza's approach to teaching music was anything but formal. At first I found it frustrating, and rather disorganized. You never knew what he might talk about next. One day he would be chalking out modes and musical terms on the blackboard. Another day he would decide to spend the whole class period telling us stories about village life in Nubia, before the Deluge: the cultural and ecological catastrophe of the Aswan Dam. A calamity which literally drowned the Nubian way of life, and destroyed a culture which had existed at least since the time of the Pharaohs --- yet a calamity which also allowed me to meet this exile who would change my life, like so many others who encountered him. This became evident even in his class at UT. Many rich and otherwise improbable friendships were formed among us through his influence. Because of Hamza, I met my lifelong friend Geoffrey von Menken, classical scholar, musiciologist, and master luthier, who made the superb oud I still play today.

I remember being impressed by one of his stories about how Nubians handled theft --- a phenomenon extremely rare in his village, Toshka. People never locked their houses. They didn't even have locks, though they had poor and prosperous people living together, like villages everywhere. They had no jail. Sometimes people would return home after an absence to find that a sack of rice had disappeared. But no one worried. In a day or so, the person who took it would appear, with an explanation of need, and a promise to pay it back. But on the rare occasions when it became clear that someone had actually stolen something, it also became clear to everyone who the thief was. Somehow, all the villagers knew. And the thief knew that they knew. The punishment? No one would talk to the thief. People deliberately avoided the person. It didn't take long for this punishment to have its effect: either the thief would leave and never return, or (more often) would break into tears and ask forgiveness. Which was always granted, providing the debt was honored.

There were so many other stories. And jokes. About life, about music, about dervishes, Islam and other religions, the effect of modern times... it would take a book for me to do justice to them. Finally, I began to understand that telling stories was an essential element of his teaching of music.

As well as the group classes, I signed up for individual oud classes with him (the drumming lessons took place in the group classes). Formally, I studied with him for almost two years. I learned to play and improvise in the maqamat (like modes, or ragas) of Arabic classical music. But I could have learned that elsewhere. The precious thing he gave me was a radically different approach to music. How to sum it up? "Spiritual" seems a bit of a cliché, but I don't know if I can find a better expression. I'd been encouraged by other musical teachers who perceived some talent in me, but Hamza encouraged me in a totally new way. He deeply perceived how much my playing tended to come from the head and the hands more than from the heart, and he gently urged me to always go back to my own heart, and to the heart of the music. To find deep relaxation in all my body, even (paradoxically) in the midst of intense activity. And never underestimate the value of simplicity! He also told me that whether I am playing repertoire, improvising, or composing, I should try to remember that I am only the instrument. God is the real musician. It has taken me decades to digest all this, and the process is still far from complete.

In the many years since our first meeting, our friendship became like a diamond in my life. Not that I got to see the diamond all that often. Sometimes years would go by without any contact between us, any news from him. He wasn't much of a correspondent. Once when I happened to be in San Franciso in the late '70s, he suddenly called me up and invited me to join his group onstage with the Grateful Dead, clapping the complex 48-beat cycle of the Nubian "Nagrisad" to Hamza's tar drum, singing, and Mickey Hart's percussion. It was the Dead's last concert at the old Winterland palace. Then I didn't see him for a long time, and heard he'd moved to Japan. But we always connected again, sooner or later, somewhere or other. Everytime we talked on the phone, or met (in Austin, in California, and in more recent years when he played in Paris, where I now live with my wife, singer Catherine Braslavsky) his magnificent smile, warm embrace, and teasing jokes made it seem as if no time had passed at all. It was in Paris, when he was playing in "The Persians" by Peter Sellars, that we first met his wife, Nabra. She's Japanese, but her name is Nubian, and means "pure gold" --- she has been a delight to get to know. As the years go by, I sometimes meet people connected with Hamza in some way I never knew of. A recent example is Fikri El Kashef, a Nubian musician who has known Hamza longer than anyone else I've met. Fikri is the director of an extraordinary "ecolodge" near Abu Simbel in Egypt, highly recommended for anyone traveling to Egypt, and a destination in itself. (See link here.) It is called Eskaleh --- an alternate spelling of Escalay, The Water Wheel, powerful symbol of ancient Nubian life, and the title of Hamza's most original and perhaps most profound album. Fikri is also a world-class musician, though he has recorded very little that I know of. His style of oud playing leans more toward the Arab virtuosic traditions than Hamza's but his Nubian roots are deep nevertheless. I was amazed to hear a homemade recording of Hamza and Fikri playing Escalay in an oud duo, with a very deep communication between them ... something I would have thought virtually impossible, because of the nature of that composition.

Because we live in a time of unprecedented evolutionary crisis, I'd like to add another half-forgotten memory, which I hadn't thought about for years, until I began to write this. It must have been sometime in the mid-70's. Hamza had been visiting Austin for a concert, and I think he stayed over for a visit and to give a lecture. He, Geoffrey, and I were having supper at a sandwich shop. We were talking about some of the esoteric teachings that were beginnng to proliferate in those times --- Sufi, Zen, Tibetan, Yoga, etc... All three of us had just read the first Seth books by Jane Roberts, and were discussing that extraordinary material. After a reflective pause, Hamza said:

"I wonder why all these teachings, which used to be so rare, are now being published for everyone? It's amazing to me. So many bookstores have them. Why is this happening now?"

An answer began to form immediately in my mind. In those days I was part of the majority who were worried about nuclear holocaust, as well as the minority who were already beginning to be worried about ecology. I often felt pessimistic. I told him I thought it was because the planetary situation is becoming urgent. "We now have the capability of destroying our planet, and we need all the wisdom we can get." And then I launched into a litany of the latest statistical horrors and projections. A long silence. Then I looked at Hamza. It was as if fire were coming out of his eyes. He spoke with quiet intensity, and anger:

"No! This thing you call planet is the mother of life. They will not destroy her. SHE will destroy them! The Earth will rise up and destroy all their technology and all their cities if she has to! "

I had never seen Hamza so fierce. Nor had I heard him speak about the Earth in this way. Geoffrey and I were silent.

Then, as I recall, he quietly added something like this: "It is only by the mercy of God, er-Rahman, er-Rahim, that it hasn't happened yet."

Last, but far from least: I learned something precious and inexpressible about the tasawwuf, the Sufi Way, from Hamza. Not that he claimed to be a Sufi master. It was what he manifested, what he incarnated, more than what he said. Once, he told me: "If you ever hear anyone say 'I am a Sufi', it means they're not." Some years later, I became deeply attracted to the books of Idries Shah. I mentioned to Hamza that I had learned from Shah's writings that the word "faqir" is originally an Arabic word, meaning simply "poor person" And that the concept became greatly distorted in India, with all the strange antics we associate with "fakirs". I was rather excited about this discovery. He agreed that the Indian version is a weird distortion of the original meaning. But he laughed a lot at my excitement about the etymology. "Did you know, Yusuf, that I'm a faqir ? Yes, it's almost like a family name. People don't call me Hamza El Din at home, they call me Hamza Faqir."

The faqir ideal is said to be this: never to look up to anyone whose social status is above yours, and never to look down on anyone whose social status is below yours. Hamza lived this ideal.

I feel grief, and joy, in writing this memoir .... I dedicate it to all who loved Hamza and love his music, and to his beloved Nabra....

as-salaamu'aleikum ... shalom aleichem... Peace to all

May all beings awaken to the Truth of who they are ...

Yusuf

(as Hamza always called me.)